4 The Gambler’s Fallacy

Applied statistics is hard.

—Andrew Gelman

My wife’s family keeps having girls. My wife has two sisters and she and her sisters each have two daughters, with no other siblings or children. That’s nine girls in a row!

Note that girl and boy aren’t the only possibilities. The next child could also be intersex, like fashion model Hanne Gaby Odiele.

So are they due for a boy next? Here are three possible answers.

- Answer 1. Yes, the next baby is more likely to be a boy. Ten girls in a row would be a really unlikely outcome.

- Answer 2. No, the next baby is actually more likely to be a girl. Girls run in the family! Something about this family clearly predispose them to have girls.

- Answer 3. No, the next baby is equally likely to be a boy vs. girl. Each baby’s sex is determined by a purely random event, similar to a coin flip. So it’s equal odds every time. The nine girls so far is just a coincidence.

Which answer is correct?

4.1 Independence

It all hangs on whether the sex of each baby is “independent” of the others. Two events are independent when the outcome of one doesn’t change the probability of the other.

A clear example of independence is sampling with replacement. Suppose we have an urn with \(50\) black marbles and \(50\) white ones. You draw a ball at random, then put it back. Then you give the urn a good hard shake and draw at random again. The two draws are independent in this case. Each time you draw, the number of black vs. white marbles is the same, and they’re all randomly mixed up.

Even if you were to draw ten white balls in a row, the eleventh draw would still be a \(50\)-\(50\) shot! It would just be a coincidence that you drew ten white balls in a row. Because there’s always an even mix of black and white marbles, and you’re always picking one at random.

But now imagine sampling without replacement. The situation is the same, except now you set aside each ball you draw rather than put it back. Now the draws are dependent. If you draw a black ball on the first draw, the odds of black on the next draw go down. There are only \(49\) black balls in the urn now, vs. \(50\) white.

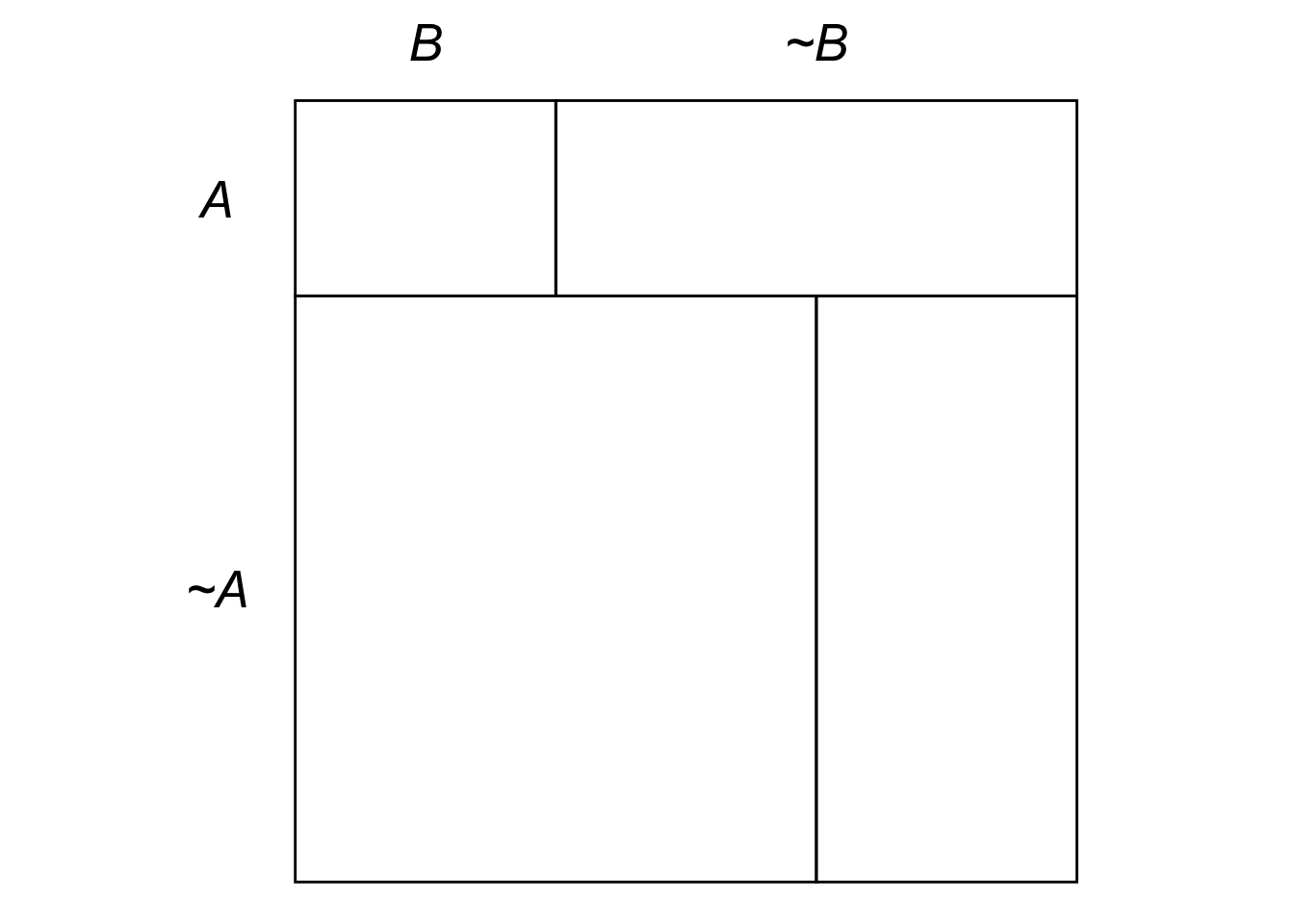

Figure 4.1: Example of an eikosogram.

Figure 4.1: Example of an eikosogram.

We can visualize independence with an eikosogram, which is like an Euler diagram but with rectangles instead of circles. The size of each sector reflects its probability. For example, in Figure 4.1 the proposition \(A \wedge B\) has low probability (\(1/12\)), while \(\neg A \wedge B\) has much higher probability (\(1/2\)).

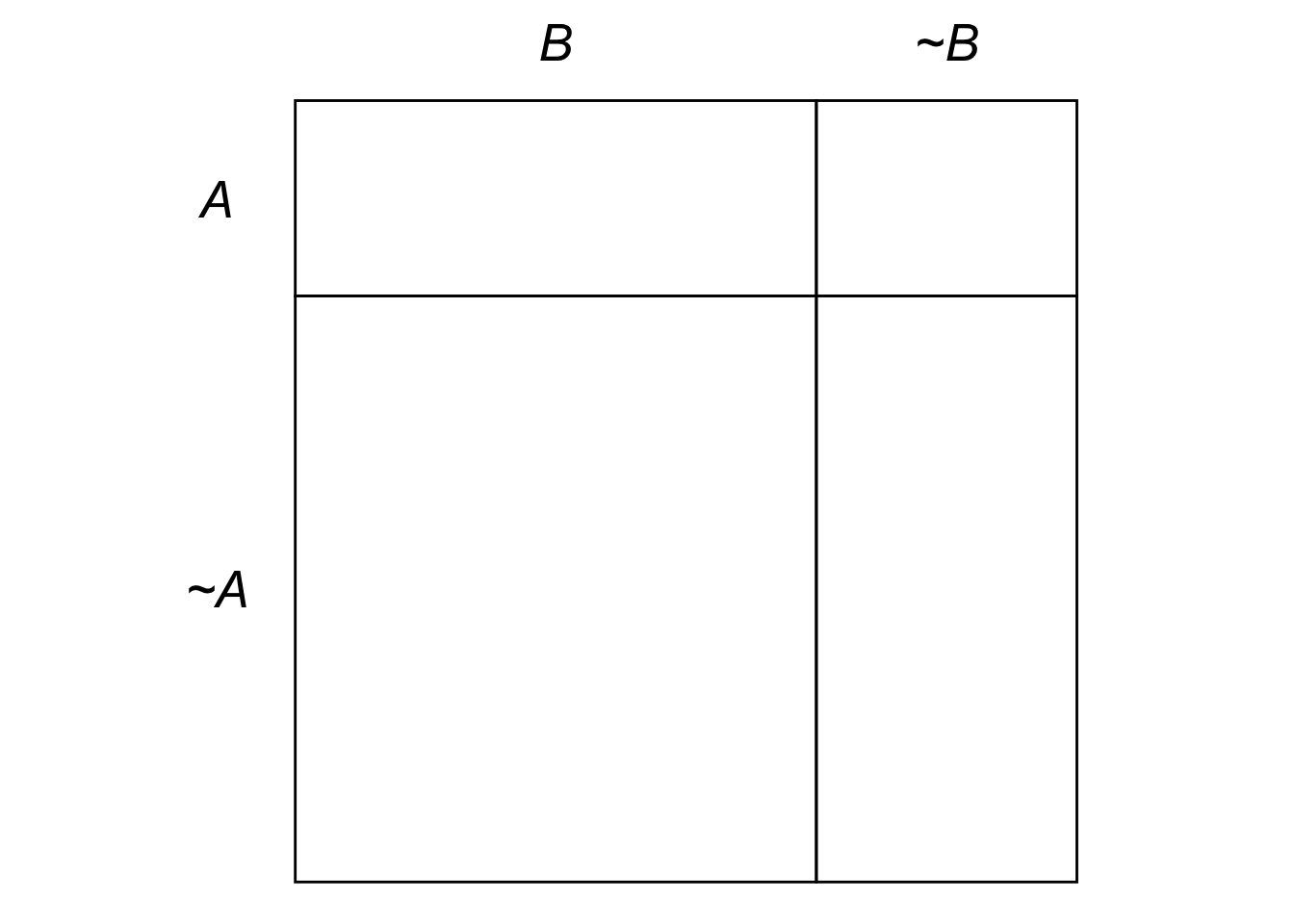

Figure 4.2: Example of an eikosogram where \(A\) and \(B\) are independent.

Figure 4.2: Example of an eikosogram where \(A\) and \(B\) are independent.

When propositions are independent, as in Figure 4.2, the eikosogram is divided by just two straight lines. That way the \(A\) region takes up the same percentage of the \(B\) region as it does the \(\neg B\) region. So the probability of \(A\) is the same whether \(B\) is true or false. In other words, \(B\)’s truth has no effect on the probability of \(A\).

4.2 Fairness

Flips of an ordinary coin are also independent. Even if you get ten heads in a row, the eleventh toss is still \(50\)-\(50\). If it’s really an ordinary coin, the ten heads in a row was just a coincidence.

Coin flips aren’t just independent, they’re also unbiased: heads and tails are equally likely. A process is biased if some outcomes are more likely than others. For example, a loaded coin that comes up heads \(3/4\) of the time is biased.

So coin flips are unbiased and independent. We call such processes fair. \[ \mbox{Fair = Unbiased + Independent}.\] Another example of a fair process is drawing from our black/white urn with replacement. There are \(50\) black and \(50\) white marbles on every draw, so black and white have equal probability every time.

But drawing without replacement is not a fair process, because the draws are not independent. Removing a black ball makes the chance of black on the next draw go down.

4.3 The Gambler’s Fallacy

Gambling often involves fair processes: fair dice, fair roulette wheels, fair decks of cards, etc. But people sometimes forget that fair processes are independent. If a roulette wheel comes up black nine times in a row, they figure it’s “due” for red. Or if they get a bunch of bad hands in a row at poker, they figure they’re due for a good one soon.

“Simply cannot stop thinking about a girl I knew who dated a guy she couldn’t STAND—all because his ex died in a plane crash, & her biggest fear was dying in a plane crash, & she figured there was no way the universe would let both of this guy’s girlfriends die in a plane crash” —@isabelzawtun.

This way of thinking is called the gambler’s fallacy. A fallacy is a mistake in reasoning. The mistake here is failing to fully account for independence. These gamblers know the process in question is fair, in fact that’s a key part of their reasoning. They know it’s unlikely that the roulette wheel will land on black ten times in a row because a fair wheel should land on black and red equally often. But then they overlook the fact that fair also means independent, and independent means the last nine spins tell us nothing about the tenth spin.

The gambler’s fallacy is so seductive that it can be hard to find your way out of it. Here’s one way to think about it that may help. Imagine the gambler’s point of view at two different times: before the ten spins of the wheel, and after. Before, the gambler is contemplaing the likelihood of getting ten black spins in a row:

\[ \_ \, \_ \,\_ \,\_ \,\_ \,\_ \,\_ \,\_ \,\_ \,\_ \, ? \]

From that vantage point, the gambler is exactly right to think it’s unlikely these ten spins will all land on black. But now imagine their point of view after observing (to their surprise) the first nine spins all landing black:

\[ B \, B \, B \, B \, B \, B \, B \, B \, B \, \_ \,? \]

Now how likely is it these ten spins will all land black? Well, just one more spin has to land black now to fulfill this unlikely prophecy. So it’s not such a long shot anymore. In fact it’s a \(50\)-\(50\) shot. Although it was very unlikely the first nine spins would turn out this way, now that they have, it’s perfectly possible the tenth will turn out the same.

4.4 Ignorance Is Not a Fallacy

At this point you may have a nagging thought at the back of your mind. If we flipped a coin \(100\) times and it landed heads every time, wouldn’t we conclude the next toss will probably land heads? How could that be a mistake?!

The answer: it’s not a mistake. It would be a mistake if you knew the coin was fair. But if you don’t know that, then \(100\) heads in a row could be enough to convince you it’s actually not fair.

The gambler’s fallacy only occurs when you know a process is fair, and then you fail to reason accordingly. If you don’t know whether a process is fair, then you aren’t making a logical error by reasoning according to a different assumption.

So, is the gambler’s fallacy at work if my wife’s family expects a boy next? As it turns out, the process that determines the sex of a child is pretty much fair.2 The question isn’t completely settled though, as far as I could tell from my (not very thorough) research. So the correct answer to our opening question was Answer 3.

Most people don’t know about the relevant research, though. They may (like me) only know a bit from high school biology about how sex is usually determined at conception. But it’s still possible for all they know that some people’s eggs are more likely to select sperm cells with an X chromosome, for example.

So it’s not necessarily a fallacy if my in-laws expect a boy next. It could just be a reasonable conclusion given the information available. A fallacy is an error in reasoning, not a lack of knowledge.

4.5 The Hot Hand Fallacy

Sometimes a basketball player hits a lot of baskets in a row and people figure they’re on fire: they’ve got a “hot hand.” But a famous study published in 1985 found that these streaks are just a coincidence. Each shot is still independent of the others. Is the hot hand an example of the gambler’s fallacy?

Most people don’t know about the famous 1985 study. Certainly nobody knew what the result of the study would be before it was conducted. So a lot of believers in the hot hand were in the unfortunate position of just not knowing a player’s shots are independent. So the hot hand isn’t the same as the gambler’s fallacy.

Believers in the hot hand may be guilty of a different fallacy, though. That same study analyzed the reasoning that leads people to think a player’s shots are dependent. Their conclusion: people tend to see patterns in sequences of misses and hits even when they’re random. So there may be a second, different fallacy at work, the “hot hand fallacy.”

Things might actually be even more complicated than that, though. Some recent studies found that the hot hand may actually be real after all! How could that be possible? What did the earlier studies miss?

It’s still being researched, but one possibility is: defense. When a basketball player gets in the zone, the other team ups their defense. The hot player has to take harder shots. So one of the recent studies added a correction to account for increased difficulty. And another looked at baseball instead, where they did find evidence of streaks.

But here’s Selena Gomez and Nobel prize winner Richard Thaler telling a bit of the story in a clip from the 2015 movie The Big Short.

The full story of the hot hand fallacy has yet to be told it seems.

Exercises

Suppose you are going to draw a card at random from a standard deck. For each pair of propositions, say whether they are independent or not.

\(A\): the card is red.

\(B\): the card is an ace.\(A\): the card is red.

\(B\): the card is a diamond.\(A\): the card is an ace.

\(B\): the card is a spade.\(A\): the card is a Queen.

\(B\): the card is a face card.

After one draw with replacement, drawing a second marble from an urn filled with \(50\) black and \(50\) white marbles is a ______ process.

- Independent

- Fair

- Unbiased

- All of the above

- None of the above

After one draw without replacement, drawing a second marble from an urn filled with \(50\) black and \(50\) white marbles is a ______ process.

- Independent

- Fair

- Unbiased

- All of the above

- None of the above

For each of the following examples, say whether it is an instance of the gambler’s fallacy.

You’re playing cards with your friends using a standard, randomly shuffled deck of \(52\) cards. You’re about half-way through the deck and no aces have been drawn yet. You conclude that an ace is due soon, and thus the probability the next card is an ace has gone up.

You’re holding a six-sided die, which you know to be fair. You’re going to roll it \(60\) times. You figure about \(10\) of those rolls should be threes. But after \(59\) rolls, you’ve rolled a three only five times. You figure that the probability of a three on the last roll has gone up: it’s higher than just \(1/6\).

You know the lottery numbers in Ontario are selected using a fair process. So it’s really unlikely that someone will win two weeks in a row. Your friend won last week, so you conclude their chances of winning this week too are even lower than usual.

You’re visiting a new country where corruption is common, so you aren’t sure whether the lottery there is fair. You see on the news that the King’s cousin won the lottery two weeks in a row. You conclude that their chances of winning next week are higher than normal, because the lottery is rigged in their favour.

Suppose \(A\) and \(B\) are compatible (not mutually exclusive). Does it follow that they are independent? If your answer is yes, explain why this follows. If your answer is no, give a counterexample (an example where \(A\) and \(B\) are neither mutually exclusive nor independent).

Suppose \(A\) is independent of \(B\), and \(B\) is independent of \(C\). Does that mean \(A\) is independent of \(C\)? If yes, justify your answer. If no, describe a counterexample (an example where it’s false).