17 Dutch Books

As to the speculators from the south, they had the advantage in the toss up; they said heads, I win, tails, you lose; they could not lose any thing for they had nothing at stake.

—Newspaper report, Sep. 2, 1805

Critics of Bayesianism won’t be satisfied just because beliefs can be quantified with betting rates. After all, a person’s betting rates might not obey the laws of probability. What’s to stop someone being \(9/10\) confident it will rain tomorrow and also \(9/10\) confident it won’t rain? How do we enforce the laws of probability, like the Negation Rule, if probability is just subjective opinion?

17.1 Dutch Books

The Bayesian answer uses a special betting strategy. If someone violates the laws of probability, we can use this strategy to take advantage of them. We can sucker them into a deal that will lose them money no matter what.

“A bet is a tax on bullshit.” —Alex Tabarrok

For example, suppose Sam violates a very simple rule of probability. His personal probability in the proposition \(2+2=4\) is only \(9/10\), when it should be \(1\). (Because it’s impossible for \(2+2\) to be anything other than \(4\).) Sam has violated the laws of probability, so he’ll be willing to accept a very bad deal, as follows.

We put two marbles into an empty bucket, and then two more. We then offer Sam the following deal: we pay him \(90\)¢, and in exchange he pays us \(\$1\) if the bucket has a total of \(4\) marbles in it.

This deal should be fair according to Sam. As he sees it, there’s a \(90\%\) chance he’ll have to pay us \(\$1\) for a net loss of \(10\)¢. But there’s also a \(10\%\) chance he won’t have to pay us anything, a net gain of \(90\)¢. So the expected value is zero according to Sam’s personal probabilities: \[ (9/10)(-\$.10) + (1/10)(\$.90) = 0. \] And yet, Sam will lose money no matter what! There’s no way for him to win: he’s bound to end up paying out \(\$1\), when we only paid him \(90\)¢ to get in on the deal.

This kind of deal is called a Dutch book.7 Why is it called that? The ‘book’ part comes from gambling, where ‘making a book’ means setting up a betting arrangement. But the ‘Dutch’ part is a mystery. A Dutch book has two defining features.

- The arrangement is fair according to the subject’s personal probabilities.

- The subject will lose money no matter what.

If you are vulnerable to a Dutch book, then it looks like there’s something very wrong with your personal probabilities. A deal looks fair to you when it clearly isn’t. It’s impossible for you to win!

Almost nobody in real life would be foolish enough accept the deal we just offered Sam. Real people have enough sense not to violate the laws of probability in such obvious ways. But there are subtler ways to violate the laws of probability, which people do fall prey to. And we can create Dutch books for them too.

17.2 The Bankteller Fallacy

Consider a famous problem.

This problem was devised by the same psychologists who studied the taxicab problem: Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. This one is from a 1983 study of theirs.

Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken, and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in anti-nuclear demonstrations. Which is more probable?

- Linda is a bank teller.

- Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement.

In psychology experiments, almost everyone chooses (2). But that can’t be right, and you don’t need to know anything about Linda to prove it.

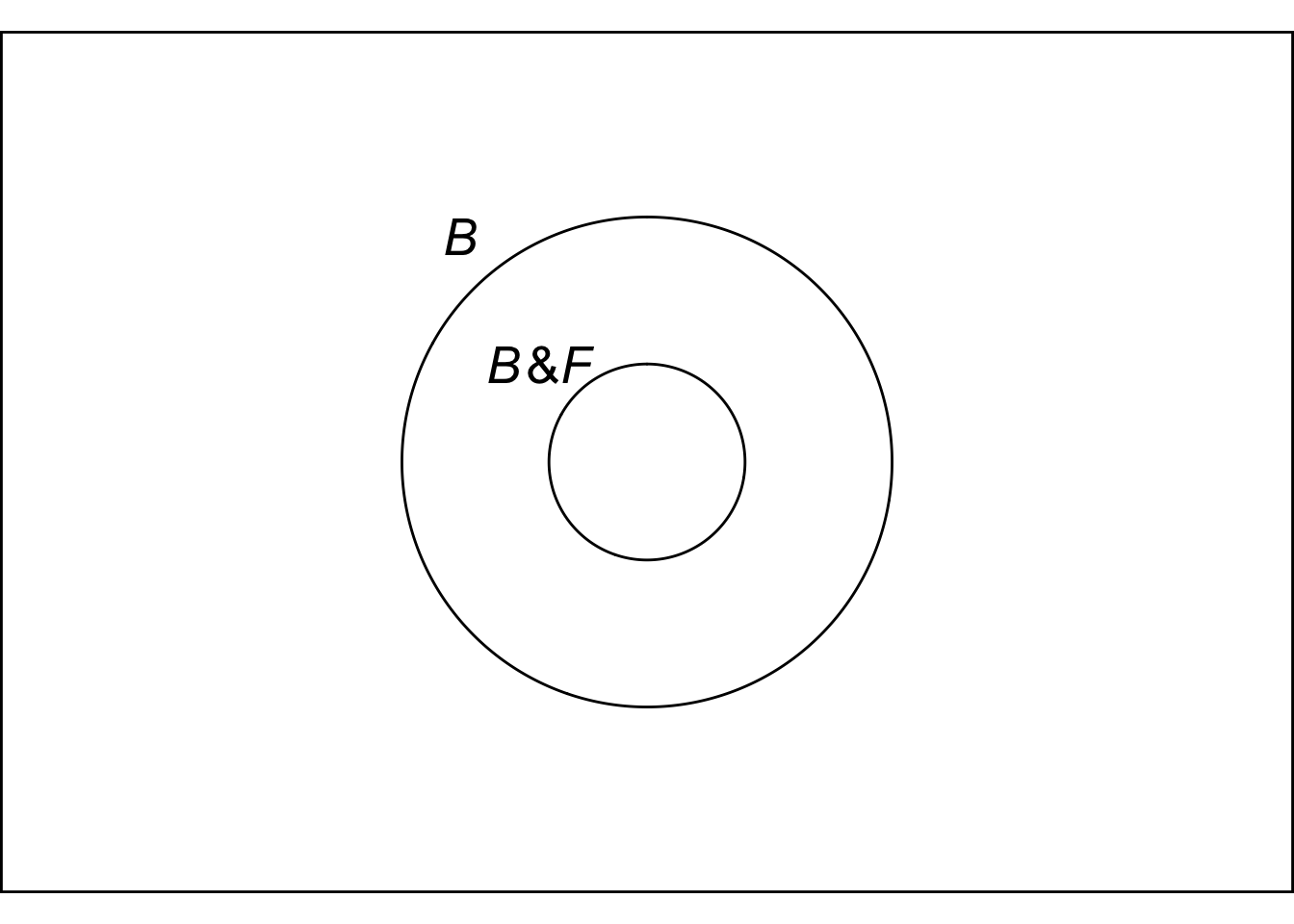

Figure 17.1: Bank tellers and feminist bank tellers

Figure 17.1: Bank tellers and feminist bank tellers

In general, the probability of a conjunction \(B \wedge F\) cannot be greater than the probability of \(B\). There are simply more possibilities where \(B\) is true than there are possibilities where both \(B\) and \(F\) are true. Figure 17.1 illustrates the point.

So it’s a law of probability that \(\p(B \wedge F) \leq \p(B)\). Which means it can’t be more likely that Linda is both a bankteller and a feminist than that she is a bankteller.

Here’s another way to think about it. Imagine everyone who fits the description of Linda gathered in a room. The people in the room who happen to be bank tellers are then gathered together inside a circle. Some of the people inside that circle will also be feminists. But there can’t be more feminists inside that circle than people! Feminist bank tellers are just less common than bank tellers in general.

How do we Dutch book someone who mistakenly thinks \(B \wedge F\) is more probable than \(B\)? We offer them two deals, one involving a bet on \(B\) and the other a bet on \(B \wedge F\).

Suppose for example their betting rate for \(B\) is \(1/5\), and their betting rate for \(B \wedge F\) is \(1/4\). Then we offer them these deals:

- We pay them \(20\)¢, and in exchange they agree to pay us \(\$1\) if \(B\) is true.

- They pay us \(25\)¢, and in exchange we agree to pay them \(\$1\) if \(B \wedge F\) is true.

Both of these deals are fair according to their betting rates. So our victim will be willing accept both. And yet, they’ll lose money no matter what. Why?

Notice how they’ve already paid us more than we’ve paid them, before the bets are even settled. We’re up \(5\)¢ from the get-go. So for them to come out ahead, they’ll have to win the second bet. But if they do win the second bet, we win the first bet. They only win the second bet if \(B \wedge F\) is true, in which case \(B\) is automatically true and we win the first bet. Since both bets pay off \(\$1\), they cancel each other out.

Thinking through a Dutch book can be tricky, but a table like 17.1 can help. The columns are the possible outcomes, the rows are exchanges of cash. For clarity, we separate investments and returns into their own rows. The investment is the amount the person pays or receives at first, when the bet is arranged. The return is the amount they win/lose if the bet pays off. The last row sums up all the investments and returns to get the net amount won or lost.

Table 17.1: A Dutch book for the bank teller fallacy

| \(B \wedge F\) | \(B \wedge \neg F\) | \(\neg B\) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bet \(1\) | Investment | \(\$0.20\) | \(\$0.20\) | \(\$0.20\) |

| Return | \(-\$1.00\) | \(-\$1.00\) | \(\$0.00\) | |

| Bet \(2\) | Investment | \(-\$0.25\) | \(-\$0.25\) | \(-\$0.25\) |

| Return | \(\$1.00\) | \(\$0.00\) | \(\$0.00\) | |

| Net | \(-\$0.05\) | \(-\$1.05\) | \(-\$0.05\) |

Notice how the net amount is negative in every column. In a Dutch book, no matter what, the victim loses money.

17.3 Dutch Books in General

Anyone who violates any law of probability can be suckered via a Dutch book. But if you obey the laws of probability, it’s impossible to be Dutch booked. That’s why the laws of probability are objectively correct, according to Bayesians.

Bruno de Finetti (1906–1985) proved in the \(1930\)s that the laws of probability are the only safegaurd against Dutch books. The same point was also noted by Frank Ramsey in an essay from the \(1920\)s, though he didn’t include a proof.

What’s the general recipe for constructing a Dutch book when someone violates the laws of probability?

First, use bets with a \(\$1\) stake. That makes things simple, because the victim’s personal probability will be the same as their fair price for the bet. If their personal probability is \(1/2\), they’ll be willing to pay \(50\)¢ for a bet with a \(\$1\) payoff. If their personal probability is \(1/4\), they’ll be willing to pay \(25\)¢ for a bet with a \(\$1\) payoff. And so on.

Second, remember that if a bet is fair then a person should be willing to take either side of the bet. Suppose they think it’s fair to pay \(25\)¢ in exchange for \(\$1\) if \(A\) turns out to be true. Then they should also be willing to accept \(25\)¢ instead, and pay you \(\$1\) if \(A\) turns out to be true. It’s a fair bet, so either side should be acceptable.

Third is the trickiest bit. Which propositions should you get them to bet on, and which should you get them to bet against? Think about which propositions they are overconfident of, and which they are underconfident of.

For example, Sam was underconfident in \(2+2=4\). He was only \(9/10\) confident instead of \(1\). So we underpaid him for a bet on that proposition: \(90\)¢ in exchange for \(\$1\) if it was true. His underconfidence meant he was willing to accept too little in exchange for a \(\$1\) payout.

Whereas in the bank teller example, the victim was overconfident of \(B \wedge F\), and underconfident in \(B\). So we underpaid them for a bet on \(B\), and got them to overpay us for a bet on \(B \wedge F\).

Here’s one more example. Suppose Suzy the Scientist is conducting an experiment. The experiment could have either of two outcomes, \(E\) or \(\neg E\). Suzy thinks there’s a \(70\%\) chance of \(E\), and a \(40\%\) chance of \(\neg E\). She’s violated the Additivity rule: \(\p(E) = 7/10\) and \(\p(\neg E) = 4/10\), which adds up to more than \(1\).

So we can make a Dutch book against Suzy. In this case she’s overconfident in both of the propositions \(E\) and \(\neg E\). So we get her to overpay us for bets on \(E\) and on \(\neg E\).

- Suzy pays us \(70\)¢, and in exchange we pay her \(\$1\) if \(E\) is true.

- Suzy pays us \(40\)¢, and in exchange we pay her \(\$1\) if \(\neg E\) is true.

The end result is that Suzy loses \(10\)¢ no matter what. At the beginning she pays us \(\$0.70 + \$0.40 = \$1.10\). Then she wins back \(\$1\), either for the bet on \(E\) or for the bet on \(\neg E\). But in the end, she still has a net loss of \(10\)¢.

Table 17.2: A Dutch book for Suzy the Scientist

| \(E\) | \(\neg E\) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bet \(1\) | Investment | \(-\$0.70\) | \(-\$0.70\) |

| Return | \(\$1.00\) | \(\$0.00\) | |

| Bet \(2\) | Investment | \(-\$0.40\) | \(-\$0.40\) |

| Return | \(\$0.00\) | \(\$1.00\) | |

| Net | \(-\$0.10\) | \(-\$0.10\) |

We now have a second way for Bayesians to argue that the concept of personal probability is scientifically respectable. Not only can beliefs be quantified. There are also objective rules that everyone’s beliefs should follow: the laws of probability. Anyone who doesn’t follow those laws can be suckered into a sure loss.

Exercises

Suppose Ronnie has personal probabilities \(\p(A) = 4/10\) and \(\p(\neg A) = 7/10\). Explain how to make a Dutch book against Ronnie. Your answer should include all of the following:

- A list of the bets to be made with Ronnie.

- An explanation why Ronnie will regard these bets as fair.

- An explanation why these bets will lead to a sure loss for Ronnie no matter what.

Suppose Marco has personal probabilities \(\p(X) = 3/10\), \(\p(Y) = 2/10\), and \(\p(X \vee Y) = 6/10\). Explain how to make a Dutch book against him. Your answer should include all of the following:

- A list of the bets to be made with Marco.

- An explanation why Marco will regard these bets as fair.

- An explanation why these bets will lead to a sure loss for Marco no matter what.

Maya is the star of her high school hockey team. My personal probability that she’ll go to university on an athletic scholarship is \(3/5\). But because she doesn’t like schoolwork, my personal probability that she’ll go to university is \(1/3\). Explain how to make a Dutch book against me.

Saia isn’t sure what grade she’ll get in her statistics class. But she thinks the following deals are all fair:

- If she gets at least a B+, you pay her \(\$2\); otherwise she pays you \(\$5\).

- If she gets a B+, you pay her \(\$6\); otherwise she pays you \(\$1\).

- If she gets a B+, B, or B-, you pay her \(\$5\); otherwise she pays you \(\$2\).

Assume that utility and money are equal for Saia.

- What is Saia’s personal probability that she’ll get at least a B+?

- What is Saia’s personal probability that she’ll get a B or a B-?

- True or false: given the information provided about Saia’s fair betting rates, there is a way to make a Dutch book against her.

Cheryl isn’t sure what the weather will be tomorrow, but she thinks the following deals are both fair:

- If it rains, you pay her \(\$3\); otherwise she pays you \(\$7\).

- If it rains or snows, she pays you \(\$8\); otherwise you pay her \(\$2\).

Assume that utility and money are equal for Cheryl.

- What is Cheryl’s personal probability that it will rain?

- What is Cheryl’s personal probability that it will rain or snow?

- True or false: given the information provided about Cheryl’s fair betting rates, there is a way to make a Dutch book against her.

Silvio can’t find his keys. He suspects they’re either in his car or in his apartment. His personal probability is \(6/10\) that they’re in one of those two places. But he searched his car top to bottom and didn’t find them, so his personal probability that they’re in his car is only \(1/10\). On the other hand, his apartment is messy and most of the time when he can’t find something, it’s buried somewhere in the apartment. So his personal probability that the keys are in his apartment is \(3/5\). Explain how to make a Dutch book against Silvio.

Suppose my personal probability for rain tomorrow is \(30\%\), and my personal probability for snow tomorrow is \(40\%\). Suppose also that my personal probability that it will either snow or rain tomorrow is \(80\%\). Explain how to make a Dutch book against me.

Piz’s personal probability that Pia is a basketball player is \(1/4\). His probability that she’s a good basketball player is \(1/3\). Explain how to make a Dutch book against Piz.

Consider these two statements:

- If someone’s degrees of belief violate a law of probability, then they can be Dutch booked.

- If someone can be Dutch booked, then their degrees of belief violate a law of probability.

Which one of the following is correct?

- Only (i) is true.

- Only (ii) is true.

- Both (i) and (ii) are true.

- Neither is true.

Suppose \(A\) and \(B\) are compatible propositions. True or false: if someone has personal probabilities \(\p(A \wedge B) = \p(A \vee B)\), then they can be Dutch booked.

Suppose a fair coin will be flipped twice. You and I have flipped this coin many times before, so we know that it is fair. But Frank doesn’t know about our experiments; in fact he suspects the coin is not fair. His personal probabilities are as follows: \[\begin{align*} \p(H_1 \wedge H_2) &= 3/10, \\ \p(H_1 \wedge T_2) &= 2/10, \\ \p(T_1 \wedge H_2) &= 2/10, \\ \p(T_1 \wedge T_2) &= 3/10. \end{align*}\] Assume we can only make two bets with Frank, a bet on \(H_1\) and a bet on \(H_2\). The stake for each bet must be \(\$1\). What is the most we can win from him in a Dutch book? In other words, what is the maximum amount we can guarantee we will win from him? (Note that this is different from the maximum we might win from him if we get lucky with the coin flips.)

- \(\$1\)

- \(\$0.50\)

- \(\$0.40\)

- \(\$0\): we cannot make a Dutch book against Frank