One of my favourite probability puzzles to teach is a close cousin of the Monty Hall problem. Originally from a 1965 book by Frederick Mosteller,1 here’s my formulation:

Three prisoners, A, B, and C, are condemned to die in the morning. But the king decides in the night to pardon one of them. He makes his choice at random and communicates it to the guard, who is sworn to secrecy. She can only tell the prisoners that one of them will be released at dawn.

Prisoner A welcomes the news, as he now has a 1/3 chance of survival. Hoping to go even further, he says to the guard, “I know you can’t tell me whether I am condemned or pardoned. But at least one other prisoner must still be condemned, so can you just name one who is?”. The guard replies (truthfully) that B is still condemned. “Ok”, says A, “then it’s either me or C who was pardoned. So my chance of survival has gone up to ½”.

Unfortunately for A, he is mistaken. But how?

Update: turns out the puzzle isn’t originally due to Mosteller after all! It appears in a 1959 article in Scientific American, by Martin Gardner.

For me it’s really intuitive that A is mistaken. The way he figures things, his chance of survival will go up to ½ whoever the guard names in her response. But then A doesn’t even have to bother the guard. He can just skip ahead to the conclusion that his chance of survival is ½. And that’s absurd.

It’s a bit harder to say exactly where A goes wrong. But I’ve always taken this puzzle to be, like Monty Hall, a lesson in Carnap’s TER: the Total Evidence Requirement.

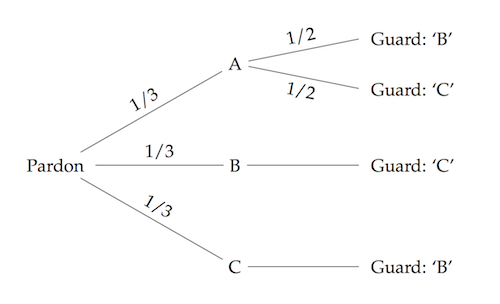

What A learns isn’t only that B is condemned, but also that the guard reports as much. And this report is more likely if C was pardoned than if A was. If C was pardoned, the guard had to name B, the only other prisoner still condemned. Whereas if A was pardoned, the guard could just as easily have named C instead.

So when the guard names B, her report fits twice as well with the hypothesis that C was pardoned, not A:

Thus A’s chance of being condemned remains twice that of being pardoned.

If you’re like me, this reasoning will actually be less intuitive than the initial, gut feeling that A must be mistaken (because her logic would make it unnecessary to consult the guard). The argument is still instructive though, for several reasons:

It shows how the initial, gut feeling is consistent with the probability axioms. We’ve constructed a plausible probability model that vindicates it.

The Total Evidence Requirement makes the difference in this model. Learning merely that B is condemned would have a different effect in this model. A’s chance of survival really would go up to ½ then.

These lessons can be carried over to Monty Hall. The same model yields the correct solution there, with the TER playing out in a parallel way.

And that last point is the real point of this post. As my colleague Sergio Tenenbaum pointed out in conversation, it means you can use Mosteller’s puzzle to teach Monty Hall. Because, unlike in Monty Hall, the intuitive judgment is the correct one in Mosteller’s puzzle. So you can use it to get students on board with the less intuitive (but entirely correct) argument we used to resolve Mosteller’s puzzle.

Once students have seen how important it is to set up the probability model correctly, so that the Total Evidence Requirement can do its work, they may be more comfortable using the same technique on Monty Hall.

There are other ways of bringing students around to the correct solution to Monty Hall, of course. You can run them through a variant with a hundred doors instead of three; you can invite them to consider what would happen in the long run in repeated games; you can ask them how things would have been different had Monty opened the other door instead.

These are all worthy heuristics. And I expect different ones will click for different students.

But for my money, there’s nothing like a simple and concrete model to help me get oriented and shake off that befuddled feeling. And, in this case, Mosteller’s puzzle helps make the model more intuitive, hence more memorable.

- So I think it actually predates Monty Hall, though I gather this general family of puzzles goes back at least to 1889 and Bertrand’s box paradox. [return]