Does an author’s gender affect the fate of their submission to an academic journal? It’s a big question, even if we restrict ourselves to philosophy journals.

But we can make a start by using Ergo as one data-point. I’ll examine two questions:

Question 1: Does gender affect the decision rendered at Ergo? Are men more likely to have their papers accepted, for example?

Question 2: Does gender affect time-to-decision at Ergo? For example, do women have to wait longer on average for a decision?

Background

Some important background and caveats before we begin:

Our data set goes back to Feb. 11, 2015, when Ergo moved to its current online system for handling submissions. We do have records going back to Jun. 2013, when the journal launched. But integrating the data from the two systems is a programming hassle I haven’t faced up to yet.

We’ll exclude submissions that were withdrawn by the author before a decision could be rendered. Usually, when an author withdraws a submission, it’s so that they can resubmit a trivially-corrected manuscript five minutes later. So this data mostly just gets in the way.

We’ll also exclude submissions that were still under review as of Jan. 1, 2017, since the data there is incomplete.

The gender data we’ll be using was gathered manually by Ergo’s managing editors (me and Franz Huber). In most cases we didn’t know the author personally. So we did a quick google to see whether we could infer the author’s gender based on public information, like pronouns and/or pictures. When we weren’t confident that we could, we left their gender as “unknown”.

This analysis covers only men and women, because there haven’t yet been any cases where we could confidently infer that an author identified as another gender. And the “gender unknown” cases are too few for reliable statistical analysis.

Since we only have data for the gender of the submitting author, our analysis will overlook co-authors.

With that in mind, a brief overview: our data set contains $696$ submissions over almost two years (Feb. 11, 2015 up to Jan. 1, 2017), but only $639$ of these are included in this analysis. The $52$ submissions that were in-progress as of Jan. 1, 2017, or were withdrawn by the author, have been excluded. Another $5$ cases where the author’s gender was unknown were also excluded.

Gender & Decisions

Does an author’s gender affect the journal’s decision about whether their submission is accepted? We can slice this question a few different ways:

Does gender affect the first-round decision to reject/accept/R&R?

Does gender affect the likelihood of desk-rejection, specifically?

Does gender affect the chance of converting an R&R into an accept?

Does gender affect the ultimate decision to accept/reject (whether via an intervening R&R or not)?

The short answer to all these questions is: no, at least not in a statistically significant way. But there are some wrinkles. So let’s take each question in turn.

First-Round Decisions

Does gender affect the first-round decision to reject/accept/R&R?

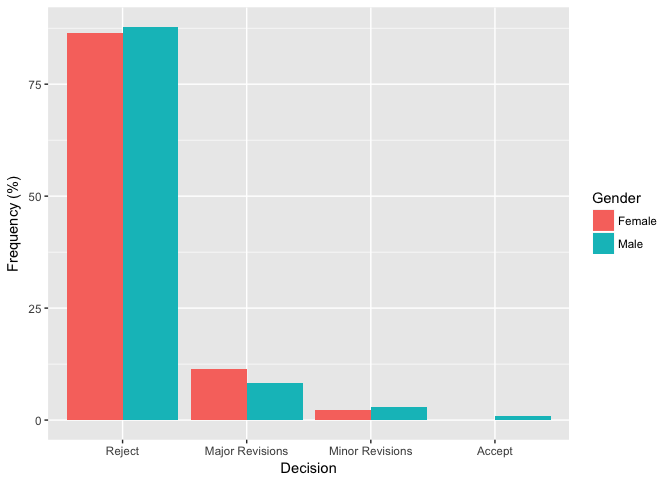

Ergo has two kinds of R&R, Major Revisions and Minor Revisions. Here are the raw numbers:

| Reject | Major Revisions | Minor Revisions | Accept | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 76 | 10 | 2 | 0 |

| Male | 438 | 41 | 15 | 5 |

Graphically, in terms of percentages:

There are differences here, of course: women were asked to make major revisions more frequently than men, for example. And men received verdicts of minor revisions or outright acceptance more often than women.

Are these differences significant? They don’t look it from the bar graph. And a standard chi-square test agrees.1

Desk Rejections

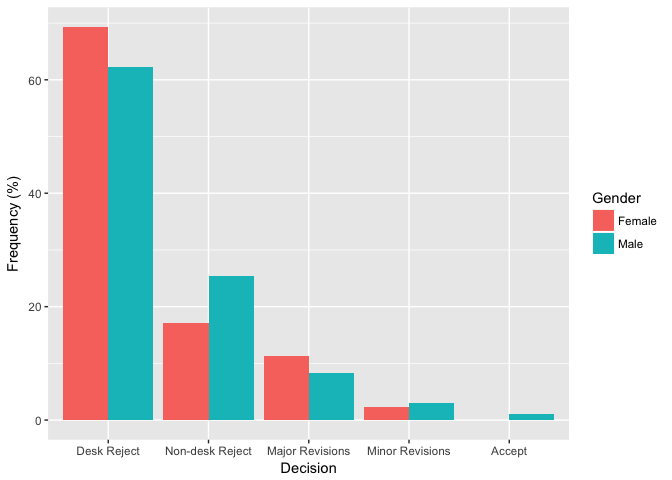

Things are a little more interesting if we separate out desk rejections from rejections-after-external-review. The raw numbers:

| Desk Reject | Non-desk Reject | Major Revisions | Minor Revisions | Accept | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 61 | 15 | 10 | 2 | 0 |

| Male | 311 | 127 | 41 | 15 | 5 |

In terms of percentages for men and women:

The differences here are more pronounced. For example, women had their submissions desk-rejected more frequently, a difference of about 8.5%.

But once again, the differences are not statistically significant according to the standard chi-square test.2

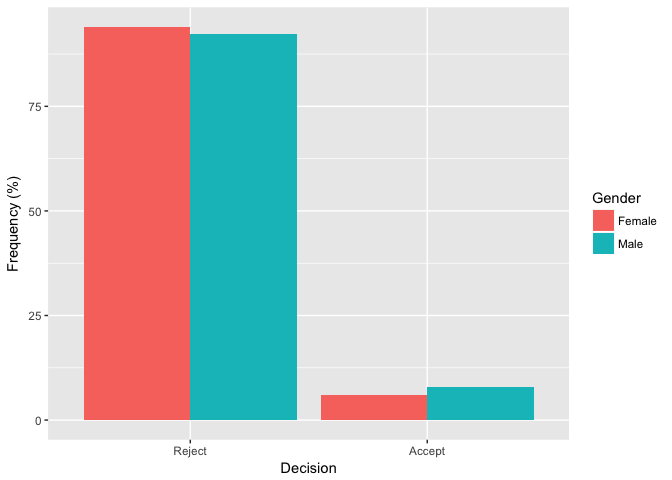

Ultimate Decisions

What if we just consider a submission’s ultimate fate—whether it’s accepted or rejected in the end? Here the results are pretty clear:

| Reject | Accept | |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 78 | 5 |

| Male | 450 | 38 |

Pretty obviously there’s no significant difference, and a chi-square test agrees.3

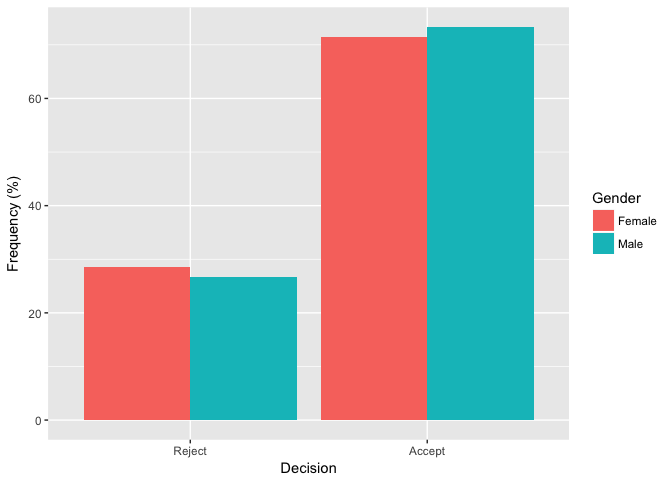

Conversions

Our analysis so far suggests that men and women probably have about equal chance of converting an R&R into an accept. Looking at the numbers directly corroborates that thought:

| Reject | Accept | |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 2 | 5 |

| Male | 12 | 33 |

As before, a standard chi-square test agrees.4 Though, of course, the numbers here are small and shouldn’t be given too much weight.

Conclusion So Far

None of the data so far yielded a significant difference between men and women. None even came particularly close (see the footnotes for the numerical details). So it seems the journal’s decisions are independent of gender, or nearly so.

Gender & Time-to-Decision

Authors don’t just care what decision is rendered, of course. They also care that decisions are made quickly. Can men and women expect similar wait-times?

The average time-to-decision is 23.3 days. But for men it’s 23.9 days while for women it’s only 19.6. This looks like a significant difference. And although it isn’t quite significant according to a standard $t$ test, it very nearly is.5

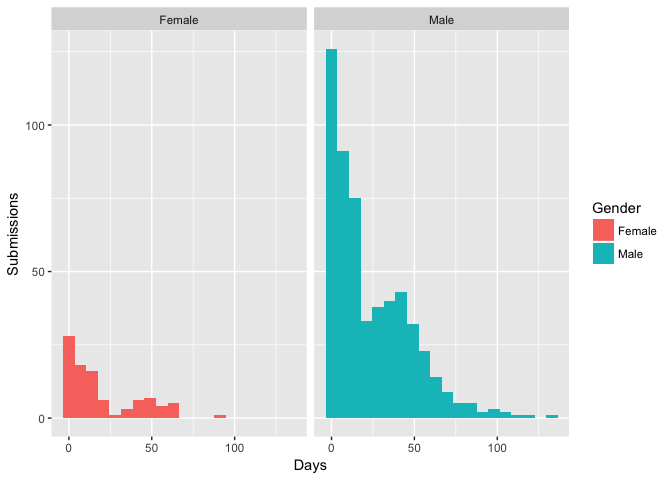

What might be going on here? Let’s look at the observed distributions for men and women:

A striking difference is that there are so many more submissions from men than from women. But otherwise these distributions actually look quite similar. Each is a bimodal distribution with one peak for desk-rejections around one week, and another, smaller peak for externally reviewed submissions around six or seven weeks.

We noticed earlier that women had more desk-rejections by about 8.5%. And while that difference wasn’t statistically significant, it may still be what’s causing the almost-significant difference we see with time-to-decision (especially if men also have a few extra outliers, as seems to be the case).

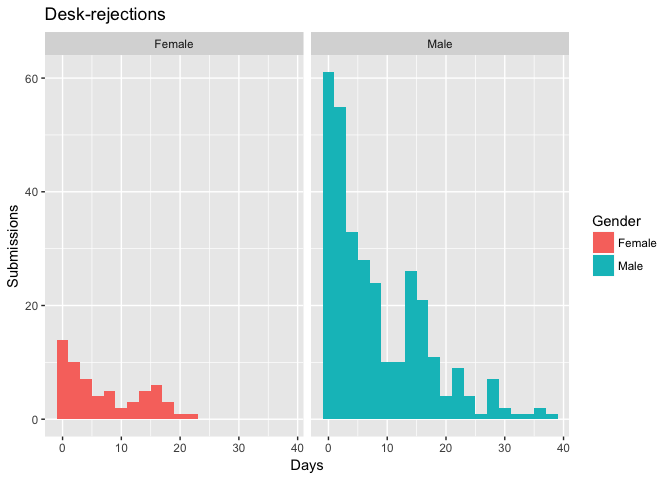

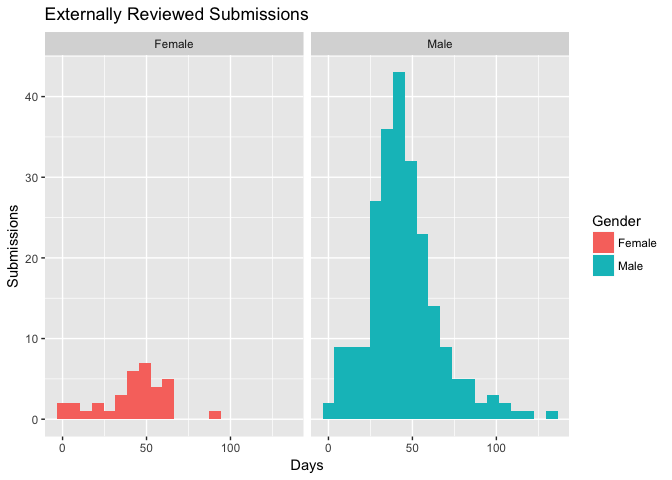

To test this hypothesis, we can separate out desk-rejections and externally reviewed submissions. Graphically:

Aside from the raw numbers, the distributions for men and for women look very similar. And if we run separate $t$ tests for desk-rejections and for externally reviewed submissions, gender differences are no longer close to significance. For desk-rejections $p = 0.24$. And for externally reviewed submissions $p = 0.46$.

Conclusions

Apparently an author’s gender has little or no effect on the content or speed of Ergo’s decision. I’d like to think this is a result of the journal’s strong commitment to triple-anonymous review. But without data from other journals to make comparisons, we can’t really infer much about potential causes. And, of course, we can’t generalize to other journals with any confidence, either.

Technical Notes

This post was written in R Markdown and the source is available on GitHub. I’m new to both R and classical statistics, and this post is a learning exercise for me. So I encourage you to check the code and contact me with corrections.

Specifically, $\chi^2(3, N = 587) = 1.89$, $p = 0.6$. This raises the question of power, and for a small effect size ($w = .1$) power is only about $0.51$. But it increases quickly to $0.99$ at $w = .2$.

Given the small numbers in some of the columns though, especially the Accept column, we might prefer a different test than $\chi^2$. The more precise $G$ test yields $p = 0.46$, still fairly large. And Fisher’s exact test yields $p = 0.72$.

We might also do an ordinal analysis, since decisions have a natural desirability ordering for authors: Accept > Minor Revisions > Major Revisions > Reject. We can test for a linear trend by assigning integer ranks from 4 down through 1 (Agresti 2007). A test of the Mantel-Haenszel statistic $M^2$ then yields $p = 0.82$.

[return]Here we have $\chi^2(4, N = 587) = 4.64$, $p = 0.33$. As before, the power for a small effect ($w = .1$) is only middling, about 0.46, but increases quickly to near certainty ($0.98$) by $w = .2$.

Instead of $\chi^2$ we might again consider a $G$ test, which yields $p = 0.24$, or Fisher’s exact test which yields $p = 0.37$.

For an ordinal test using the ranking Desk Reject < Non-desk Reject < Major Revisions < etc., the Mantel-Haenszel statistic $M^2$ now yields $p = 0.39$.

[return]- Here we have $\chi^2(1, N = 571) = 0.11$, $p = 0.74$. [return]

- $\chi^2(1, N = 52) = 0$, $p = 1$. [return]

- Specifically, $t(137.71) = 1.78$, $p = 0.08$. Although a $t$ test may not actually be the best choice here, since (as we’re about to see) the sampling distributions aren’t normal, but rather bimodal. Still, we can compare this result to non-parametric tests like Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney ($p = 0.1$) or the bootstrap-$t$ ($p = 0.07$). These $p$-values don’t quite cross the customary $\alpha = .05$ threshold either, but they are still small. [return]